An effective PM program uses a mix of different types of maintenance, and that includes corrective maintenance. As we will see in the rest of this article, you want to make sure that most, if not all, of your corrective maintenance is deferred corrective maintenance. You want to avoid emergency maintenance as much as possible because it is 3 to 5 times more expensive than properly planned work. In this article, we will talk in detail about what emergency maintenance and deferred corrective maintenance are.

Key Takeaways:

- Emergency Maintenance is 3 to 5 times more expensive than planned maintenance and should be less than 10% of your total work.

- Emergency Maintenance is the domain of the Maintenance Supervisor and the supervisor needs to manage this work using his technicians

- Keep your Maintenance Planner out of it. Do not let today’s emergencies ruin tomorrow’s productivity.

- Opting for run-to-failure means you accept failures and you are opting for deferred corrective maintenance.

- Run-to-failure is sometimes the best choice, so don’t be afraid to use run-to-failure as a valid maintenance strategy. But when you decide to use run-to-failure, it all comes down to risk management and that means you need to understand the consequences and the likelihood of the failures you’re dealing with.

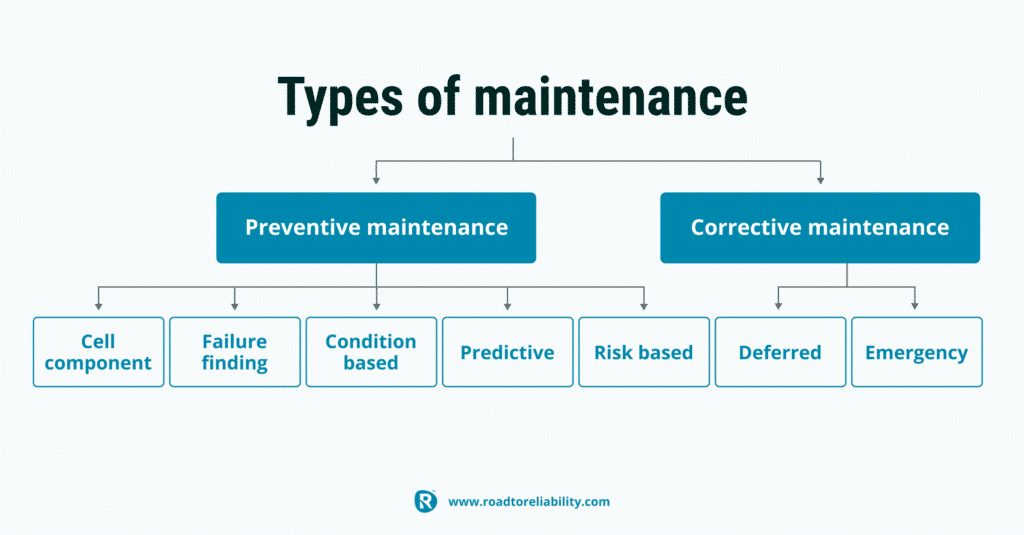

What is Corrective Maintenance

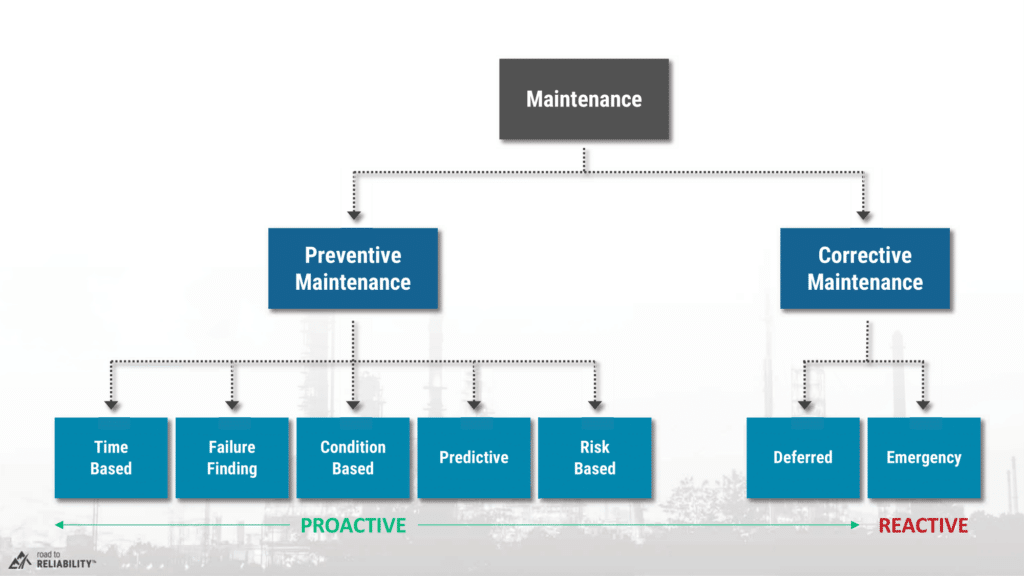

As I discussed in the article “The 9 Types of Maintenance: How to Choose the Right Maintenance Strategy”, Corrective Maintenance is any type of maintenance that is done AFTER a failure has already occurred. I broke corrective maintenance into two sub-types: Emergency Maintenance and Deferred Corrective Maintenance.

I’ll discuss each of them in greater detail throughout the rest of this article.

Let’s start with emergency maintenance.

What is Emergency Maintenance

Emergency maintenance is the kind of work that when it’s identified, is so urgent that it must be done immediately. It is new maintenance work that didn’t yet exist in the CMMS but appears in the frozen week and must be completed within that same frozen week.

And because of that, it displaces other work that was scheduled for the week. This disrupts your schedule. Instead of executing work that was properly prepared, planned, and staged—you’re now planning new work on the fly to get it done as soon as possible. That makes emergency maintenance highly inefficient and typically 3 to 5 times more expensive than properly planned work that gets executed through your frozen weekly schedule. That’s why you want to make sure this is less than 10% of your total maintenance tasks.

Emergency work is the work you want to avoid. And that’s why I emphasise proper prioritisation and the use of mitigations in the article, “You Will Fail Without Planning & Scheduling”. But despite your best efforts, emergency maintenance happens. And although our focus is to minimise it, we have to be ready to deal with it when it happens.

With that said, you need to understand WHO deals with emergency maintenance.

Who deals with Emergency Maintenance?

Now before we discuss who handles your emergency maintenance, let me be very clear:

Do NOT let your maintenance planner be involved with emergency maintenance under any circumstances.

The role of your maintenance planner is to plan future work. That is how they enable the efficiency of your whole maintenance crew. If you pull your maintenance planner away from their job to deal with today’s emergency, you won’t only have an efficiency issue today, you’re also going to have efficiency issues in the future.

And that’s exactly why I like to say—

“Don’t let today’s emergency ruin tomorrow’s productivity.”

You might be inclined to ask your planner for help to sort out issues in the current week. But don’t do it. Especially when you’re just starting out with implementing maintenance planning and scheduling. Instead, there are better ways of managing your emergency maintenance, which we discuss in our course, PS100: Implementing Maintenance Planning and Scheduling.

Alright, now that we know who doesn’t deal with your emergency maintenance. Who does deal with it? Well, it’s quite simple. It will have to be your Maintenance Supervisor supported by the maintenance crew.

Your Maintenance Supervisor runs the weekly schedule, allocates work from that schedule on a daily basis, and deals with both emergent and emergency maintenance.

How to deal with Emergency Maintenance

So how should your Maintenance Supervisor deal with emergency maintenance?

- First, someone needs to report the issue to the supervisor. That could typically be verbal or a phone call. If it’s raised through the CMMS or an email, most likely it isn’t really an emergency.

- Once the supervisor is notified, do a quick risk assessment and prioritisation. Is the risk associated with this work really big enough to justify breaking into the Frozen Weekly Schedule?

- If the supervisor does indeed believe that is the case, the next step would be to get at least a verbal agreement from whoever owns the schedule. That is typically the superintendent or plant manager. Now sometimes, they can be difficult to get a hold of and so the supervisor may have to make that decision him or herself.

- The last step is to simply start making the repair. That means planning the job on the fly and getting labor, tools, and materials organised.

If this failure occurred before, then use existing job plans and records if you can. That’s going to save you a lot of time and reduce the chance of mistakes being made.

Entering the job into the CMMS can typically be done after the job is completed, given the urgent nature of the task. But you may need to get a work order number in place so you can check out materials from the warehouse and have contractors book time against the job.

One thing to be very clear: don’t compromise on safety.

Just because it’s an emergency repair does not mean you suddenly no longer follow basic safety requirements. No job is that important that you don’t have the time to do it safely. So don’t compromise on things like having the correct PPE for the job, having the right isolations in place, or the correct permit to work. Those are absolute givens, and you must make sure that’s the case.

What is Deferred Corrective Maintenance

Now that we’ve talked about emergency maintenance, let’s discuss the next sub-type of corrective maintenance, which is Deferred Corrective Maintenance. Deferred Corrective Maintenance is a type of corrective maintenance where you deliberately let the failure happen. Unlike emergency maintenance, deferred corrective maintenance is properly planned, prioritised, staged, and kitted. It is a failure that is not urgent and therefore can be deferred to a later date so that we can properly prepare for it.

Run-to-failure should lead to Deferred Corrective Maintenance

Looking back at that hierarchy of maintenance types, you can see that if you opt for run-to-failure, you are in essence opting for deferred corrective maintenance. And to be clear, a decision to apply a run-to-failure strategy should NOT lead to emergency maintenance.

When you opt for a run-to-failure maintenance strategy, that means you’ve let the failure occur and you’re no longer in the preventive domain but in the corrective domain. What is important though, is that you do not let that drive you into the reactive domain.

Keep in mind that run-to-failure is sometimes the best choice, so don’t be afraid to use it as a valid maintenance strategy. But when you decide to use run-to-failure, it all comes down to risk management. That means you need to understand the consequences and the likelihood of the failures you’re dealing with so that you remain in the proactive domain.

When is deferred corrective maintenance proactive?

Deferred corrective maintenance can only be deemed proactive if it comes from a deliberate decision and if the consequences of the failures you are allowing do not result in emergency maintenance.

So, when you consider whether a failure mode might be a candidate for run-to-failure maintenance, you need to think through the potential consequences and what these would mean for your operation.

If that failure would require an immediate repair, thus breaking into the frozen weekly schedule, then opting for run-to-failure maintenance is not the right decision. You would be deliberately driving yourself into a reactive maintenance environment, which is exactly what you should be trying to avoid.

Run-to-failure is all about Risk Management

In most cases, the decision to choose run-to-failure maintenance is determined by the consequence of failure and less by the likelihood. But what if the likelihood of failure was high and the consequences of failure were limited? That would most likely influence your decision.

That’s why when considering run-to-failure as a strategy, you need to understand both the potential consequences and the likelihood of the failure mode you’re reviewing. It might be more precise to say that run-to-failure is nothing more than good risk management.

Deciding on Run-to-failure

Now, when considering run-to-failure as an effective strategy, you need to carefully consider whether there would be any of these potential consequences:

- safety consequences,

- environmental consequences,

- reputational consequences.

In most cases, if a failure mode has any of these consequences, you would not accept a run-to-failure strategy. So, realistically, the only time you would consider a run-to-failure strategy is when it comes to a failure mode that only has financial consequences. That includes things like repair costs, the impact on production, or your operations.

But you also need to think whether there would be consequential damage. Whether letting the failure occur would lead to more significant damage to other parts of your equipment, production, production line, or plant.

If you allowed a component to fail, would that failure lead to the failure of other components? Consequential damage is something that is often overlooked, but this is where your decision to go for a run-to-failure strategy may become an expensive mistake. So, you need to keep the concept of consequential damage clear in your mind.

Examples of Run to Failure

Lighting

As a rule of thumb, any general area lighting should be run-to-failure. The only exception would be emergency lighting where you need to opt for failure-finding maintenance because the lights are not normally on.

And you would also not apply RTF for lights in special use cases. Think of lights on exhaust stacks or flares. In these kinds of services, you may well opt for time-based maintenance.

This might mean that you are deliberately over maintaining those lights, but you accept that extra cost because the consequence of failure associated with these lights are not acceptable to the business.

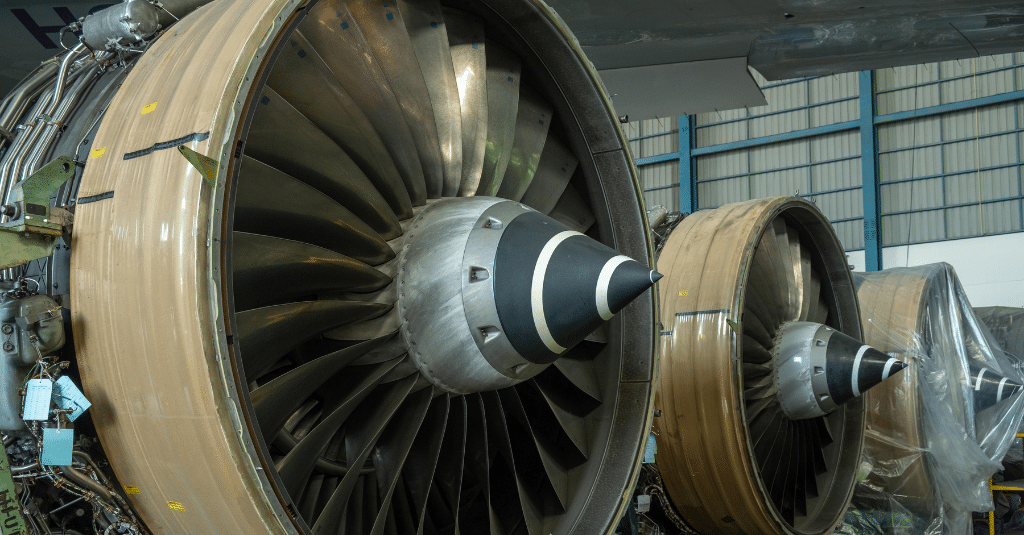

Gas Turbines

Now, whether they are attached to the wing of an airplane or sitting in a large industrial plant, these are critical, complex pieces of equipment. High value, and pretty much any kind of failure would have major impact.

So not an area where you would consider applying RTF. But I’m kind of cheating here because really you should be looking at the components of the gas turbine and their failure modes when you make these decisions.

So, although you wouldn’t run a gas turbine to failure, you may well have specific components in your gas turbine package where you do accept run-to-failure.

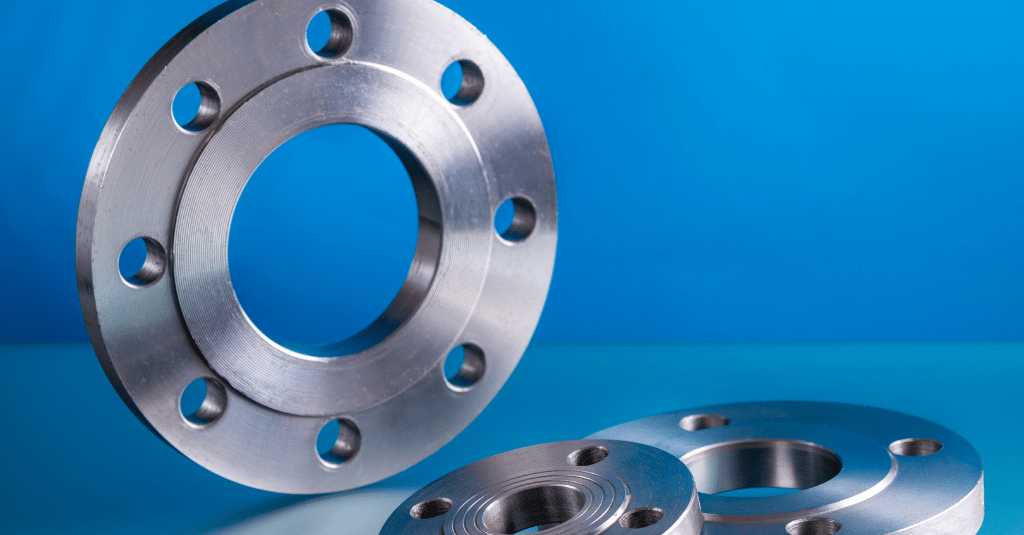

Flanges

Flanges prevent devastating consequences. But, believe me or not, these components are best handled using an RTF strategy. And that’s because the failure pattern of flanges is really one of infant mortality.

A high-quality flange that meets standard specifications and has been properly made up has a very small and constant likelihood of failure. A failure during its useful life is only going to happen if some random event occurs.

It’s all about quality management during the manufacture of the flange, having a sound flange management process, and then conducting some kind of leak testing before putting the flange into service.

That gets you through the infant mortality phase. After that, you’re dealing with a very low and constant probability of failure. And RTF becomes a very sensible strategy.

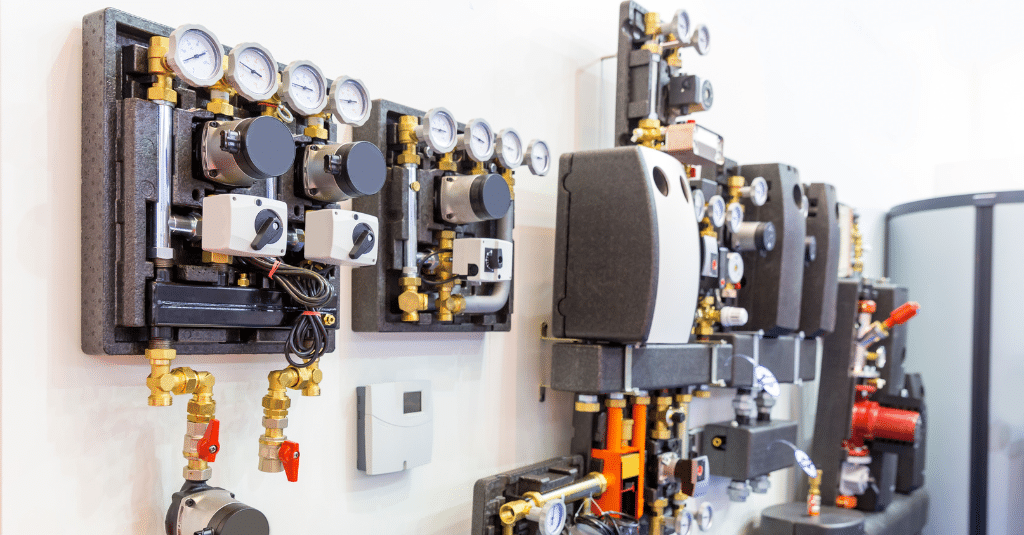

Instrumentation

In many industrial plants, you can radically reduce your instrumentation maintenance by eliminating most of your calibrations and accepting run-to-failure.

Now, of course, you can’t apply this as a blanket rule to all your process instrumentation in all industries because some instruments are critical to your operation. And Many instruments have protective functions that would require Failure Finding Maintenance (FFM).

But for the many smart process monitoring transmitters out there in your plant, RTF can be a perfectly sensible strategy. From my experience, I know you will get a fair bit of push back but don’t let that stop you!

If you’re really concerned about instrument failure, you’re probably better off using modern, smart transmitters and use the many monitoring functions they can provide (so CBM), instead of doing actual traditional, time-based calibrations.

Conclusion

Emergency maintenance should be rare, typically less than 10% of your total maintenance. We manage this through effective prioritisation, using mitigations, protecting our schedule, and ensuring emergency maintenance has to be approved by some authority.

I’ve also been clear that dealing with emergency maintenance is the domain of the maintenance supervisor and the crew. And we’re going to keep the maintenance planner out of this. We’re not going to let today’s emergency ruin tomorrow’s productivity.

Opting for run-to-failure means you accept functional failures and you are in effect opting for deferred corrective maintenance. Run-to-failure is sometimes the best choice and on occasion the only sensible choice. So don’t be afraid to use run-to-failure as a valid maintenance strategy. Run-to-failure is really about risk management and that means you need to consider both the consequences of the failures and the potential likelihood.